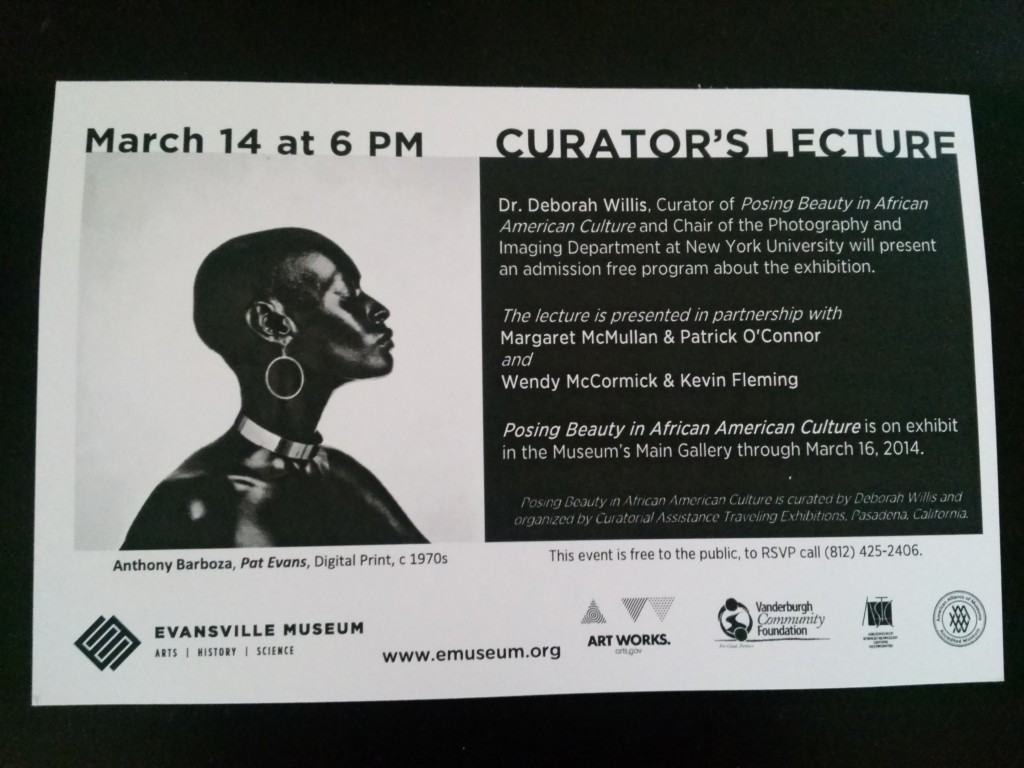

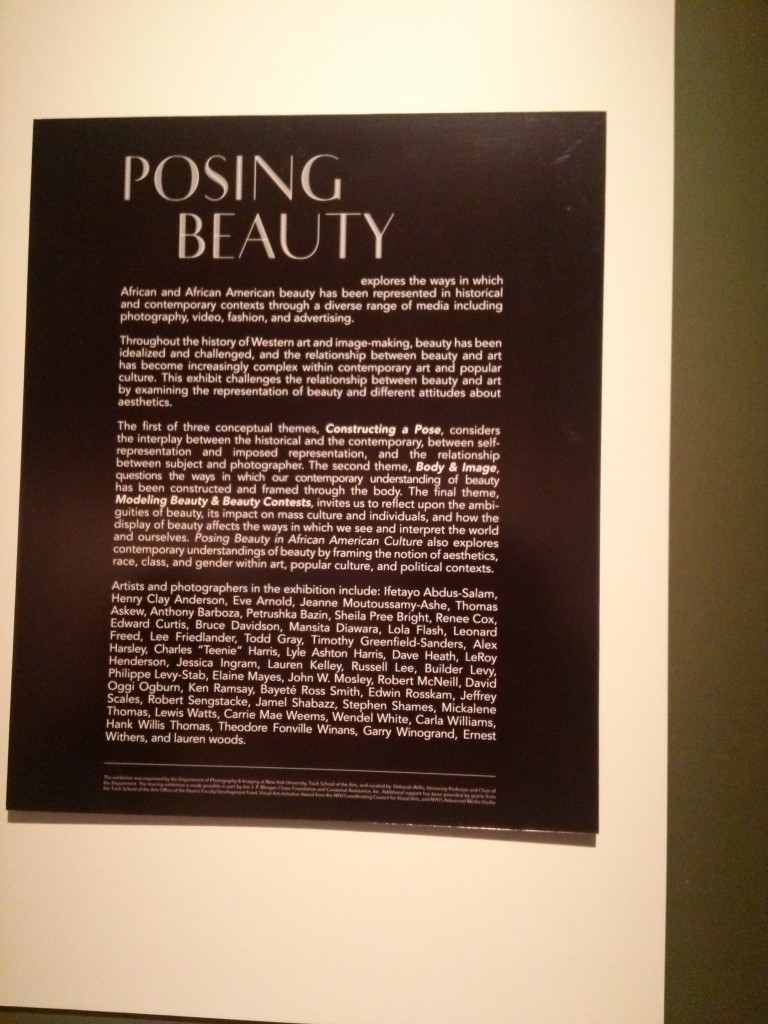

On Friday my mom and I drove up to the Evansville Museum to see the exhibit, “Posing Beauty in African American Culture.” Curated by NYU Tisch School of the Arts professor Dr. Deborah Willis, the collection of 80+ photographs from the 1890s to the 21st century “explores the ways in which African and African American beauty has been represented in historical and contemporary contexts.”

I enjoyed the exhibit because I love when the beauty of black people is upheld and when we get an opportunity to see ourselves through our own lens rather than through that of a white person exoticizing us or applying European standards of beauty to us. But “Posing Beauty” is about more than aesthetics. It is about art, history and how black people have used art (specifically photography) to try to get the world to better understand black life and acknowledge black people’s humanity.

“Young African American woman, three-quarter length portrait, facing slightly right, with hands folded on her lap,” Thomas E. Askew, 1899 or 1900. African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition, Library of Congress

For example, in the year 1900, W.E.B. DuBois presented, “The American Negro” exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. According to a description of the exhibit by the Library of Congress, “The photographs of affluent young African American men and women challenged the scientific ‘evidence’ and popular racist caricatures of the day that ridiculed and sought to diminish African American social and economic success. Further, the wide range of hair styles and skin tones represented in the photographs demonstrated that the so-called ‘Negro type’ was in fact a diverse group of distinct individuals.”

One of my favorite photos in “Posing Beauty†was this self-portrait by Carrie Mae Weems. Why? Because the title is the point of so much of the art that reflects on black life: I Looked and Looked to See What so Terrified You. Why is blackness so scary that white people can use the mere presence of black skin as a claim to self-defense? Weems is beautiful, feminine, classy and regal in the photo. Charles “Teenie” Harris’s photos of black people living their daily routines in Pittsburgh, and Edwin Rosskam’s photos of black people on Easter Sunday in New York show nothing to fear.

These days, black people–U.S.-born and not–use social media to continue to demand recognition of black beauty and humanity. On Vintage Black Glamour, Nichelle Gainer digs out archival images of successful African Americans looking their best. During the #feministselfie trend on Twitter, many black women said the selfie empowered them to feel beautiful in a world in which very few magazines and advertisements acknowledge their color and features. (Here’s a similar example.) The #DangerousBlackKids hashtag showed black children having fun with their parents, standing next to their honor roll certificates, or diving into the water during swim team practice.

Summit Avenue Ensemble, Atlanta, Georgia, Thomas E. Askew, 1899 or 1900. African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition, Library of Congress. This photograph appears in the “Posing Beauty” exhibit.

Â

I realize this is partially playing respectability politics, and I think it’s long been established that being perfect so white people don’t hurt you doesn’t work. But I see these examples from the 1890s to present day as less, “See? I’m harmless,” and more, “See? I’m human. And even if you don’t see, it doesn’t matter because I define blackness, beauty and humanity for myself.”

While black people shouldn’t have to keep repeating either of these sentiments at all in the 21st century, I’m somewhat thankful that the globalization of everything makes demonstrating the diversity and individuality of the so-called “Negro type,” easier today than it was in 1900.

I close with a trailer for “Afraid of Dark,” an upcoming documentary still looking to see what so terrifies people of black men.