Legal scholar and author Geoffrey Stone delivered the keynote address at the 2017 Woodhull Foundation Sexual Freedom Summit. Entitled, “Sex and the Constitution,” the talk was short version of his book of the same name, which was described in the workshop planner as an exploration of “the historical evolutions of religious, social, and legal approaches to sex and the role American constitutional law has played in contemporary debates over all manner of sexual mores: obscenity, contraception, abortion, and homosexuality.”

Throughout the talk, I kept waiting for him to talk about white supremacy’s role in this legal history. He didn’t.

Screenshot from the introduction to When Abortion was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973

I thought he might talk about how native peoples have been presumed savages in part because European explorers thought their “lack” of clothing was savage. I thought he might address biological theories of black hyper-sexuality in the 1700s, the fact that most black people didn’t have citizenship or personhood until the 1860s, the Dred Scott decision in which the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States wrote, “[African Americans] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, … so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” so maybe white men were more chill about brothels and prostitution because illicit sex was so readily available via the rape of enslaved black women. Maybe he’d mention lynching and explain why mobs of white men consistently got away with mutilating black men for allegedly raping white women, or that black doctor in Chicago whose name I can’t remember but who was convicted in the 1950s of performing abortions and who knew he would be when the prosecution brought up that some of his patients were white and isn’t it horrifying for a black man to see white women’s private parts? I thought I might hear about how fear of a black penis really made white legislators think, “First freedom, then citizenship, then voting rights? Next thing you know they’ll think they’re so equal they’ll want to marry white women!” Perhaps even the influx of Irish Catholic immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the anxiety that caused among white Protestants would get a nod.

Nope.

Evangelical Protestant Christianity got a lot of credit, though. And it’s not like white supremacy has ever had any role in that.

I thought maybe it was just time constraints. Then in the Q&A, someone in the audience asked what role Stone thought race and racism played in the cultural construction of sex laws. He said he didn’t think it was “a major factor.”

And just today I went to the book on Amazon to see skim the index. The terms, “African American,” “Anti-blackness,” “Race,” “Racism,” and “White supremacy” are not there. The hardcover book is 704 pages.

So I’m not buying the book. But whenever Tracie Q. Gilbert finishes her dissertation and adapts it into a book, I’m here for it. She led the session “Beyond Tuskegee: Exploring Anti-Blackness in Human Sexuality.” She hit all the points, such as Playboy’s 2008 list of human sexuality’s top 10 influencers in the U.S.

which looked different from lists people self-composed around the room, which included Beyonce, Brittney Spears, Johnny Gill, Prince, Kelly Brown Douglass, Kinsey, Masters & Johnson, James Brown, and Jesus. (Like Rev Bev’s double entendre exercise, I will need to do this list again.)

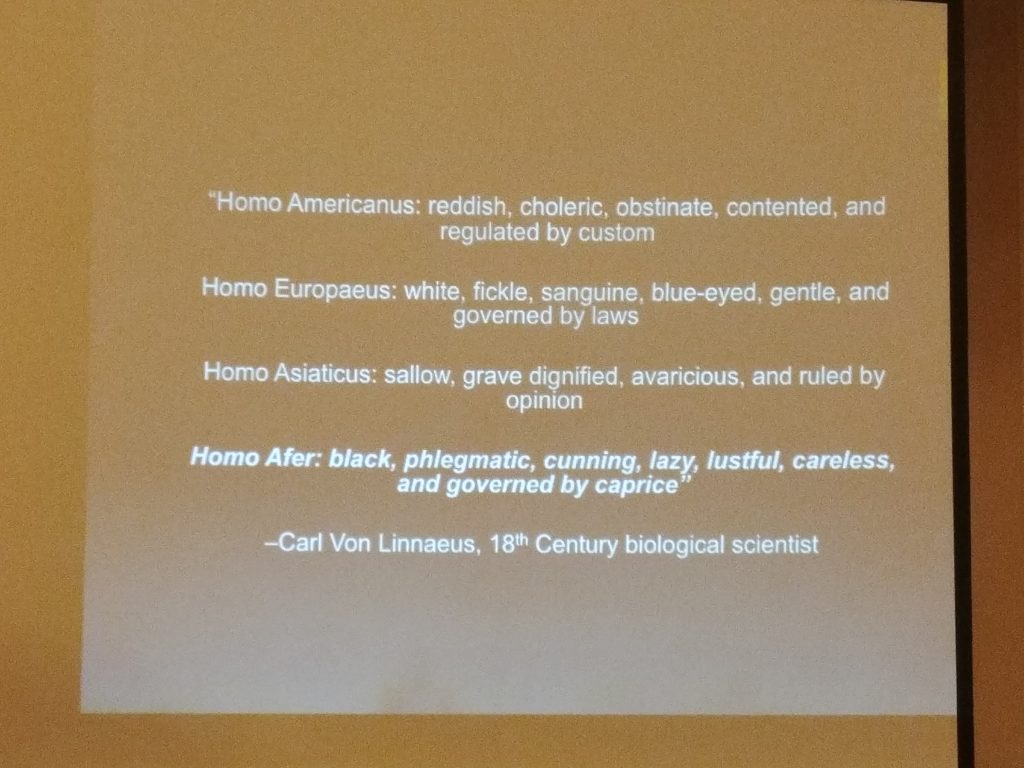

And Gilbert defined anti-blackness and some thoughts around it spoken by people in high positions in religion, government, or science.

Screenshot from Race: The History of an Idea in America. We read much of this quote out loud in Anti-Black Sex Ed

The fourth snapshot is Mississippi, 1859. That year, the Court of Appeals of Mississippi considered the case of George (a slave) v. The State.(9) In that case, a black slave named George was convicted of raping a black slave girl about nine years old. On appeal, George’s counsel argued before the court as follows:

The crime of rape does not exist in this State between African Slaves, Our laws recognize no marital status as between slaves, their sexual intercourse is left to be regulated by their owners. The regulations of law, as to the white race, on the subject of sexual intercourse, do not and cannot, for obvious reasons, apply to slaves; their intercourse is promiscuous, and the violation of a female slave by a male slave would be a mere assault and battery.

A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., “What Took Place and What Happened: White Male Domination, Black Male Domination, and the Denigration of Black Women,” in Race, Gender and Power in America: The Legacy of the Hill-Thomas Hearings, edited by Anita Faye Hill and Emma Jordan. (Gilbert showed the quote in one of her slides. I’ve copied the text here for additional context.)

Can’t imagine how any of that would’ve influenced the law.

If I hadn’t heard the Sex and the Constitution lecture the previous day, I probably would’ve felt the rage that most people in the room felt when the quotes were read. Instead I just kept hearing “not a major factor” in my head and I laughed. I had approached stone after his talk. I thought I was polite but firm in my argument that his analysis was flawed. He—an old white man who’s at least six feet tall (I just want you to picture the privilege he moves through the world with daily)—also was polite but firm in his refusal to even entertain the idea that he minimized the role of white supremacy in the formation of our nation’s sex laws. The conversation ended with me yelling, “Your privilege is showing!” as he walked away from me.

Of course, it is isn’t funny. Stone is the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law at the University of Chicago and a leading constitutional scholar. He has the attention, trust, and influence of far more people than Tracie E. Gilbert or women I’m not sure he’s read, like Ida B. Wells, Kathleen Brown, Sharon Block, Kirsten Fischer, and Martha Hodes (H/T to fine scholar Miles P. Grier for the list). He spoke at the conference of an incredibly progressive organization, where people such as Loretta J. Ross and Dr. Willie Parker also held the stage. I know that he celebrate victories for sexual freedom, but I doubt the revolutionary capacity of anyone who would minimize the force in everything white supremacy has been. The person who does that will, I believe, be okay with some of us being left out equality.

We howled, cheered, and stood when Gilbert finished her session. She’s in the study of human sexuality, not the law, but these things link, and I’m ready for more of what scholars like Gilbert will bring to the world. Also she’s doing a study. If you’re 18+, English-speaking, African American, and think about sex, fill out the study interest form.

So as not to exhaust you or myself, this is the last post about the summit but not the last it will have inspired. If it’s between Hedgebrook and Woodhull next year, you know I’m going to Hedgebrook, but if my schedule offers no conflicts, I will return for SFS18.

I’m at the Woodhull Foundation Sexual Freedom Summit this week. I’m here on a blogger’s scholarship, so I’m making time to write short insights/happenings from each day. Follow more of the conference with the hashtag #SFS17.

Very insightful. I wasn’t aware of previous issues before applying for a scholarship and attending this years conference. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for reading and for leaving a comment. What was your experience at this year’s conference? I wasn’t able to attend; I was under too much deadline pressure at the time for volunteer applications, and I couldn’t afford it otherwise.