When Cameo King sent me questions about feminism to help me prepare for this broadcast, I had to take a minute to jot down a few thoughts about what the words “feminism†and “feminist†meant to me at this point in my life. Shortly before I received the questions, I had been on the phone with a friend, mentor and supporter of my writing who had been reading my blog and was intrigued by conflicts I’ve expressed between feminism and my heart for capitalism, my desire for marriage and my Christian beliefs. She asked, “Why don’t you identify as womanist? It seems like that would solve all your problems.â€

If you return to popular memory of feminism’s second wave through the beginnings of its third, you’ll find feminism defined as a white middle-class women’s movement for economic equality and sexual freedom: white women who saw that most of their oppression had taken place in patriarchal domestic or religious spheres shed themselves of the expectations of marriage and motherhood and called on all women to do the same. Then comes Alice Walker with the term “womanist.†She says “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.†She takes the idea of women’s equality and makes it culturally specific, universalist, and spiritual—something deeper and bolder than feminism.

If you delve into more academic history of second wave feminism, it’s true you’ll find radical lesbian separatist groups and white women who failed at organizing poor women or women in communities of color in part because they didn’t understand that these women loved being wives or mothers and showed love in part by cooking or cleaning. But you’ll also find that organizations like the National Black Feminist Organization and the Third World Women’s Alliance existed and were concerned about topics such as religion, black lesbian motherhood, the depiction of blacks in the media, the decriminalization of prostitution, and fighting racism and capitalism.

This isn’t to say Walker’s definition wasn’t necessary. I’m saying defining myself as a womanist hasn’t been necessary for me. I was a precocious child, but no one ever accused me of “acting womanish.†Therefore, the cultural experience in Walker’s womanism has never resonated with me. Much of the rest of her definition works for me, though, especially #3. But I haven’t felt the need to call myself a womanist because identifying as a feminist has been enough, because I believe the same thing about feminism that I do about radical love: feminism is intersectional.

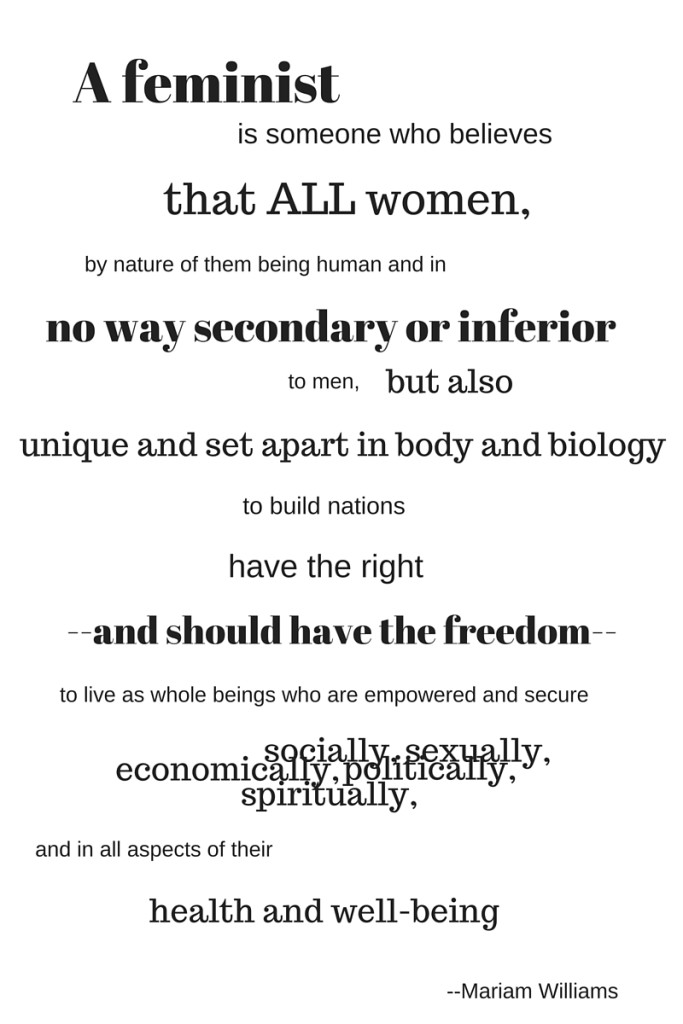

So before the broadcast, I jotted down my working definition of “feminist.†Here’s part of it. More will be unveiled and explained in the coming weeks.